How do you spot a witch? This notorious 15th-century book gave instructions – and helped execute thousands of women

(THE CONVERSATION) — Books have always had the power to cast a spell over their readers – figuratively.

But one book that was quite popular from the 15th to 17th centuries, and infamously so, is literally about spells: what witches do, how do identify them, how to get them to confess and how to bring them to swift punishment.

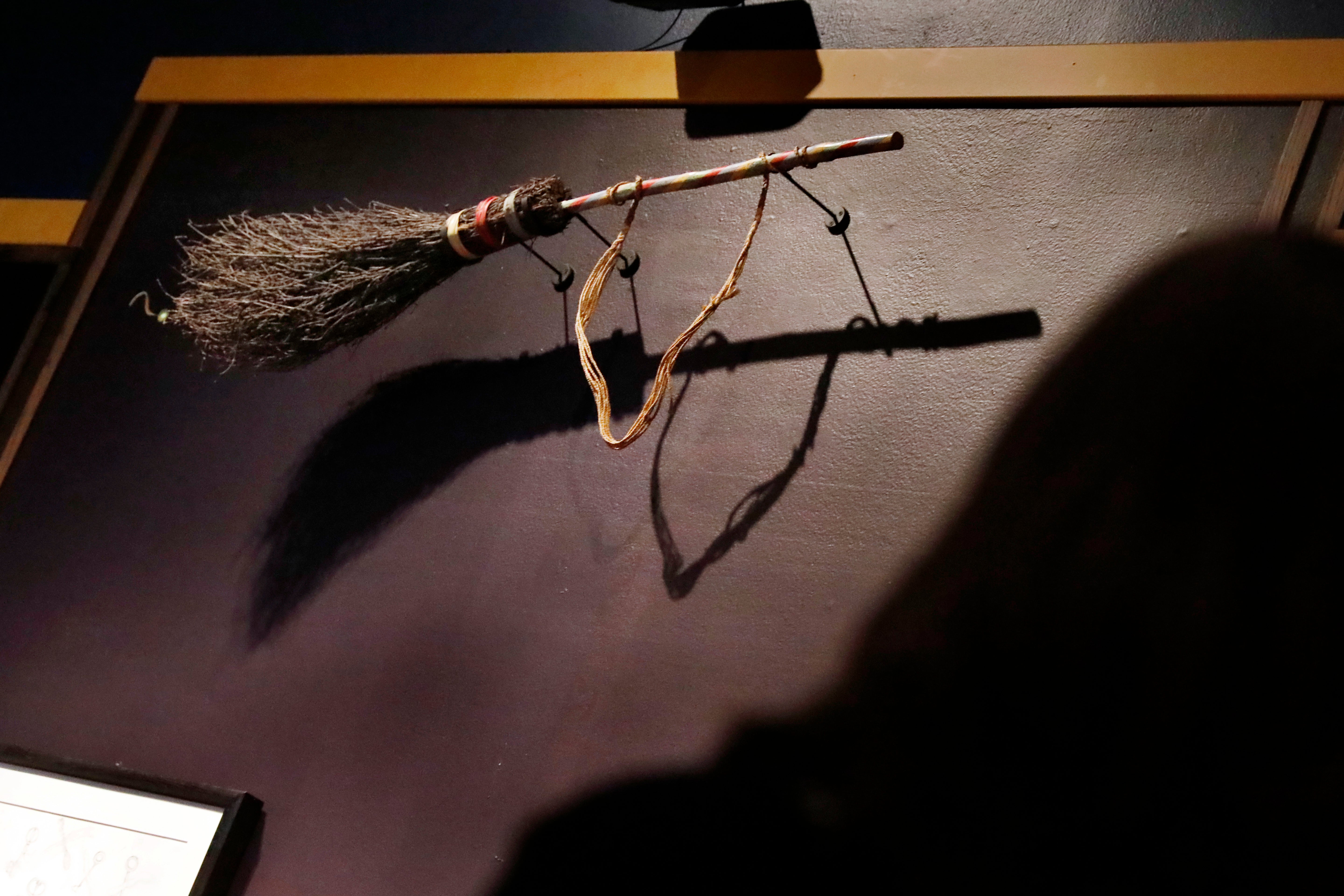

As fear of witches reached a fever pitch in Europe, witch hunters turned to the “Malleus Maleficarum,” or “Hammer of Witches,” for guidance. The book’s instructions helped convict some of the tens of thousands of people – almost all women – who were executed during the period. Its bloody legacy stretched to North America, with 25 supposed “witches” killed in Salem, Massachusetts, in the late 1600s.

“Malleus” — much has been written about the contents, but the physical book itself is a fascinating testament to history.

Witches 101

The “Malleus” was written circa 1486 by two Dominican friars, Johann Sprenger and Heinrich Kraemer, who present their guide in three parts.

The first argues that witches do in fact exist, sorcery is heresy and not fearing witches’ power is itself an act of heresy. Part Two goes into graphic detail about witches’ sexual deviancy, with one chapter devoted to “the Way whereby Witches copulate with those Devils known as Incubi.” An incubus was a male demon believed to have sex with sleeping women.

It also describes witches’ ability to turn their victims into animals and their violence against children. The third and final part gives guidelines on how to interrogate a witch, including through torture; get her to confess; and ultimately sentence her.

Twenty-eight editions of the “Malleus” were published between 1486 and 1600, making it the definitive guide on witchcraft and demonology for many years – and helping the prosecution of witches take off.

Targeting women

The authors of the text reluctantly admit that men can be agents of the devil, but argue that women are weak and inherently more sinful, making them his perfect targets.

Accusations were often rooted in the belief that women, especially those who did not submit to ideals about obedient Christian wives and mothers, were prone to be in league with the devil.

The authors detail “four horrible crimes which devils commit against infants, both in the mother’s womb and afterwards.” They even accuse witches of eating newborns and are especially suspicious of midwives.

Women on the fringes of society, such as healers in Europe or the slave Tituba in Salem, were convenient scapegoats for society’s ills.